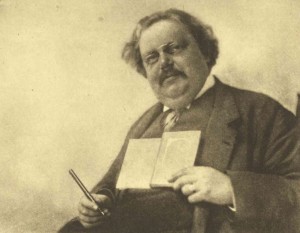

Given that Gilbert Keith Chesterton (GKC) died in 1936, some readers may be inclined to ask, “How could his views be of any value in 2020?” He himself provided the answer to that question when he wrote this in Orthodoxy (1908):

Given that Gilbert Keith Chesterton (GKC) died in 1936, some readers may be inclined to ask, “How could his views be of any value in 2020?” He himself provided the answer to that question when he wrote this in Orthodoxy (1908):

“An imbecile habit has arisen in modern controversy of saying that such and such a creed can be held in one age but cannot be held in another. Some dogma, we are told, was credible in the twelfth century, but is not credible in the twentieth. You might as well say that a certain philosophy can be believed on Mondays, but cannot be believed on Tuesdays. You might as well say of a view of the cosmos that it was suitable to half-past three, but not suitable to half-past four. What a man can believe depends upon his philosophy, not upon the clock or the century . . . Therefore in dealing with any historical answer, the point is not whether it was given in our time, but whether it was given in answer to our question.” (Emphasis added)

Here are some other insights of this great thinker about matters that at best cause us great confusion and often leave us mired in fallacy.

About the belief among many educators that understanding and wisdom lie within the child and need only to be drawn out:

“Certain crazy pedants [say that education comes] not from the outside, from the teacher, but entirely from inside the boy. Education, they say, is the Latin for leading out or drawing out the dormant faculties of each person . . . I think it would be as sane to say that the baby’s milk comes out of the baby as to say that the baby’s educational merits do . . . You may indeed ‘draw out’ squeals and grunts from the child by simply poking him and pulling him about . . . But you will wait and watch very patiently indeed before you draw the English language out of him. That you have got to put into him; and there is an end of the matter.”

About the common belief that one political party is completely wise and the other completely foolish, he reminds us that both have their failings:

“The whole modern world has divided itself into Conservatives and Progressives. The business of Progressives is to go on making mistakes. The business of the Conservatives is to prevent the mistakes from being corrected.”

About the idea that too much criticism causes division among people:

“What embitters the world is not excess of criticism, but an absence of self-criticism.”

About using the term “individual rights”to justify virtually any behavior:

“To have a right to do a thing is not at all the same as to be right in doing it.”

About the Progressives’ demand for canceling traditional things—for example, re-writing the Constitution or abolishing police departments:

“Progress should mean that we are always changing the world to fit the vision, instead we are always changing the vision.”

About the belief that criminals are not responsible because crime is a disease.

“The real objection to that torrent of modern talk about treating crime as disease, about making prison merely a hygienic environment like a hospital, of healing sin by slow scientific methods . . . is that evil is a matter of active choice whereas disease is not.”

About young people and old people disagreeing about values.

“I believe what really happens in history is this: the old man is always wrong; and the young people are always wrong about what is wrong with him. The practical form it takes is this: that, while the old man may stand by some stupid custom, the young man always attacks it with some theory that turns out to be equally stupid.” –

About the belief that all people are by nature good and it is society that is to blame for their faults:

“Original sin is really original. Not merely in theology but in history it is a thing rooted in the origins. Whatever else men have believed, they have all believed that there is something the matter with mankind.”

About the difficulty of separating credible from non-credible views:

“The man who really thinks he has an idea will always try to explain that idea. The charlatan who has no idea will always confine himself to explaining that it is much too subtle to be explained.”

About the notion that old traditions have no value today:

“Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about.”

About the tendency to worship Nature as our “mother” and, as such, a substitute for God:

“The main point of Christianity was this: that Nature is not our mother: Nature is our sister. We can be proud of her beauty, since we have the same father; but she has no authority over us; we have to admire, but not to imitate. This gives to the typically Christian pleasure in this earth a strange touch of lightness that is almost frivolity. Nature was a solemn mother to the worshipers of Isis and Cybele. Nature was a solemn mother to Wordsworth or to Emerson. But Nature is not solemn to Francis of Assisi . . . To St. Francis, Nature is a sister, and even a younger sister: a little, dancing sister, to be laughed at as well as loved.”

About the notion that religion burdens people with too many rules:

“The truth is, of course, that the curtness of the Ten Commandments is evidence, not of the gloom and narrowness of a religion, but, on the contrary, of its liberality and humanity. It is shorter to state the things forbidden than the things permitted: precisely because most things are permitted, and only a few things are forbidden.”

About the argument that Christianity has failed as a guide to living:

“The Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting; it has been found difficult and left untried.”

The last quote is so simply written that its profundity can easily be missed. In reality, it is a powerful reminder that that the faults, offenses, and sins associated with Christianity, including those of the Church hierarchy, are human failings and in no way discredit the Christian ideal. On the contrary, they confirm its importance.

Copyright © 2020 by Vincent Ryan Ruggiero. All rights reserved