Ambrose Bierce, a master of insightful wit, once defined the term Scriptures as “the sacred books of our holy religion, as distinguished from the false and profane writings on which all other faiths are based.” The sly implication that no religion has greater insight into the divine than all other religions is, of course, false—there are truths about the divine as about any other subject, and some inquirers (and religions) are more successful than others in identifying them.

Ambrose Bierce, a master of insightful wit, once defined the term Scriptures as “the sacred books of our holy religion, as distinguished from the false and profane writings on which all other faiths are based.” The sly implication that no religion has greater insight into the divine than all other religions is, of course, false—there are truths about the divine as about any other subject, and some inquirers (and religions) are more successful than others in identifying them.

Nevertheless, Bierce’s suggestion that many people define their religion as the only true religion and other religions as imposters is accurate. They may do this with substantive arguments worthy of consideration or merely because of an arrogant mine-is-better attitude—“It is impossible for my beliefs to be mistaken because they are mine”—or with a mixture of the two. In any case whenever the arrogant attitude has been present, great mischief has resulted.

One notable example is the recurring notion in many Christian churches that their interpretations of the Divine Mind are correct in every detail and therefore closed to revision, presumably even by God Himself—or to put it slightly differently, that the Holy Spirit has nothing more to reveal to mankind.

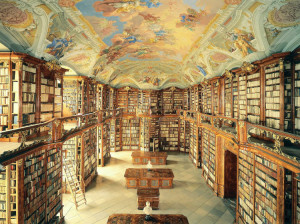

In Catholicism, over the centuries, this attitude has led to various forms of censorship, in particular the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (list of forbidden books). This list named books and/or authors that the hierarchy decided were dangerous to morals, challenged Church teachings, or both. Among the famous authors included in the list were Dante Alighieri, Galileo Galilei, Thomas Hobbes, Blaise Pascal, Rene Descartes, Francis Bacon, John Milton, John Locke, Edward Gibbon, and John Stuart Mill.

The Index was well intended. For centuries most Christians lacked sufficient education to analyze complex issues for themselves and therefore depended on educated churchmen for intellectual and spiritual guidance. Understandably, such guidance included warnings about which views were erroneous.

However, the Index was continued long after the advent of mass education. It was not discontinued until 1966 during Paul VI’s papacy, and even then not because the masses no longer needed such extreme guidance, but simply because the number of published books had grown too vast to evaluate.*

Moreover, though the listing of “forbidden books” was ended, the rule that Catholics should avoid reading such books under pain of sin remained. Thus the practice of discouraging Catholics from reading books that lacked the imprimatur (approval) of a bishop continued. (It is worth noting that for centuries Catholics were also discouraged from reading the Bible lest they be led astray by “conflicting interpretations of Scripture.” Only in 1943 did Pope Pius XII change that regulation and actually encourage Bible reading.)

Not surprisingly, for most of the last century, many conscientious Catholics felt uneasy about reading material that might in some vague way violate Catholic teaching and therefore be sinful. They also passed on that idea to their children and grandchildren. Catholic schools, too, tended to reinforce the idea. And many Catholic publishers, in an abundance of caution, decided against publishing any essays or books that the local bishop or cardinal might conceivably regard as “unorthodox.” The caution continues in some dioceses to this day and the result is that many contemporary Catholic publications tend to exclude analytical and probative writing and focus almost exclusively on celebratory or devotional material.

As a result of being conditioned to avoid controversial ideas, today’s Catholics tend to be divided into two very different groups—those who accept the hierarchy’s statements uncritically and those who ignore such statements altogether. Older Catholics tend to be in the first group; younger ones, in the second. Both groups are misguided.

Serious issues should be treated seriously by examining and evaluating all points of view fairly and forming judgments responsibly. (There are, of course, core doctrines that should be considered “settled,” but they are far fewer than commonly assumed.) All people have a moral obligation to do such thinking for themselves because God gave them each of them, individually, the priceless gifts of intellect and will.

Among the innumerable important issues that Catholics (among others) should ponder in light of their faith are the following:

What viewpoint on immigration best balances kindness to immigrants with justice to citizens?

Does the moral obligation to help one’s neighbor apply only to individuals or to governments, as well? If to both, what obligations do governments have to ensure that the money they spend is not wasted or, in the case of foreign aid, stolen by corrupt governments in other countries?

Under what circumstances, if any, is it moral for the government to conduct surveillance on its citizens without their knowledge?

For centuries, the Catholic Church was the foremost champion of reason and science. It preserved learning and scholarship during the Dark Ages, reclaimed the common sense philosophy of ancient Greece, supplanted pagan superstition with reason, inspired the Renaissance, and facilitated the rise of modern science. For this reason, the often-repeated claim that the church opposes reason and science is largely unfair. Nevertheless, as the foregoing paragraphs point out, in more recent centuries, the Church has failed to live up to the nobler aspects of its tradition.

Today, with mass culture awash in banal and inane entertainment, traditional values replaced by relativism, and rationality eroded by political correctness, Catholic men and women (with other Christians) need to play an active role in preserving the hard-won intellectual achievements of our civilization. Young Catholics must learn and be inspired by the larger, more positive role the Church has played in history. Meanwhile, older Catholics must overcome the intellectual timidity they have unfortunately been conditioned to, so they can provide the young with a positive example of mindfulness.

For this activation of intellectual energy to occur, Catholic clergy and religious and, even more importantly, bishops and cardinals, have a crucial role to play. They must acknowledge this key precept: the human intellect is a priceless gift from God to be conscientiously employed by individuals in the pursuit of truth and encouraged, rather than inhibited, by the Church. Moreover, given the laity’s deeply rooted impression that it is wrong to make full use of their intellects, it will not be sufficient for the hierarchy to let their silence imply this precept. They must proclaim it clearly and often enough for Catholics to feel comfortable in embracing and living by it.

*See L’Osservatore della Domenica 24 April 1966, pg. 10.

Copyright © 2016 by Vincent Ryan Ruggiero. All rights reserved