Even before Catholics could fully grasp the enormity of the sex abuse scandals in their church, new revelations came in waves. And they have continued. Among the latest are that the Church paid more than $4 billion in settlements and lost over $2 billion more in “lost membership and diverted giving”; that within the last year all Illinois dioceses were sued for covering up the scandal and for failure to publish the names of 500 accused priests; that eight New York dioceses were sued for withholding the names of over 400; and that Australia’s leading prelate Cardinal George Pell was found guilty of sexually abusing two 13 year-old boys.

Even before Catholics could fully grasp the enormity of the sex abuse scandals in their church, new revelations came in waves. And they have continued. Among the latest are that the Church paid more than $4 billion in settlements and lost over $2 billion more in “lost membership and diverted giving”; that within the last year all Illinois dioceses were sued for covering up the scandal and for failure to publish the names of 500 accused priests; that eight New York dioceses were sued for withholding the names of over 400; and that Australia’s leading prelate Cardinal George Pell was found guilty of sexually abusing two 13 year-old boys.

Three of the most important questions about the scandal have been thoroughly discussed: Why did the abuse occur? Why didn’t bishops take immediate action to protect the victims? What has the laity’s reaction been to the scandal? The answers to those questions have been unambiguous:

The sex abuse occurred because the sexual “revolution” that began in the 1960s encouraged people, including priests, to put feelings above moral precepts and act on their desires, even the most shameful ones. (The Church unwittingly promoted this thinking among priests and nuns by approving Humanistic Psychology and even sponsoring the “Encounter Groups” that propagandized priests and nuns.)

Bishops ignored and/or covered up the abuse because they assigned protecting the Church’s reputation a higher priority than protecting the innocent victims of abuse. (It remains unfathomable how such highly trained and anointed men could have been so woefully ignorant and/or dismissive of the Gospel and moral theology. Did they think that Jesus was joking when He promised a worse penalty than a millstone around the neck for those who harmed children? Luke 17:2)

The reaction of the laity was disgust followed by condemnation of both the abusers and the prelates that protected them, and the demand that the hierarchy take appropriate measures to end sexual abuse by priests.

But one important question has not been so thoroughly discussed and answered: What should the laity do next, after their condemnations and demands? This question came to my mind at Mass on Ash Wednesday as I pondered the ancient phrase that accompanies the anointing with ashes—“Remember man that thou art dust, and unto dust thou shalt return.”

With that question still in mind, I recalled a story I heard almost twenty years ago from an African priest who was visiting my parish. I’ll call him Father D.

Father D was one of twelve children of Congolese Catholic parents. He explained how during the political turmoil that swept his country, marauding rebels dragged his younger sister from the family home, raped and murdered her, and threw her into the river. When her body was recovered, her father did something remarkable—he immediately called together his remaining children and prayed for God to forgive the killers.

I have heard many horror stories, notably those of the Nazi Holocaust and other genocidal atrocities, and in those stories I have found many examples of forgiveness. But I cannot recall a single one of them in which the forgiveness came so quickly and offered such an inspiring example of Christlike behavior.

Father D’s story suggests an answer to what the laity should do next, after expressing their condemnations and demands. That answer is to forgive the offenders, priests and prelates alike.

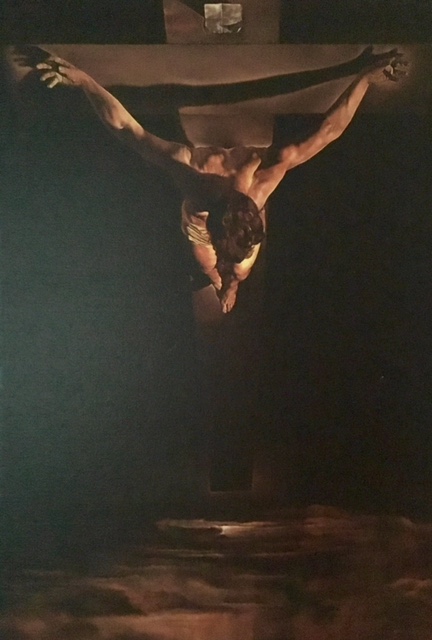

This is truly a hard saying, I know. The normal human reaction to such grave offenses is to withhold forgiveness indefinitely, perhaps forever. Yet Jesus’ life and teaching suggest a very different reaction. How many times should we forgive? Not seven but seventy times seven—in other words, so many times that we lose count. And forgive not just minor offenses or those easy to forgive, but any and all offenses. We are to forgive as Jesus forgave his persecutors while hanging on the cross, and in the way he taught us in the Our Father—to forgive as we would be forgiven.

Let’s be clear. Forgiveness does not mean approving of priests and bishops dishonoring their vows and responsibilities. Nor does it require us to place unqualified trust in their future behavior. (Doing so in the past was an unwise practice that surely enabled abusers.) The axiom, “Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me” applies here. There is no inconsistency in forgiving what was said and done in the past yet being wary in the future. Nor is it ever imprudent to challenge inappropriate behavior.

Ash Wednesday’s ashes have been washed away, but Father D’s story remains a clear and inspiring reminder of what it means to live “in imitation of Christ,” as well as a worthy guide for Catholics outraged by the sex abuse scandal.

Copyright © 2019 by Vincent Ryan Ruggiero. All rights reserved