Part 1 explained that Catholic teaching on contraception is part of the Church’s larger teaching on marriage. Both reflect the views of St. Augustine of Hippo (354-430 A.D.), who was influenced more by Manichean heresy than Christian tradition. This fact is well documented and is acknowledged by the Augustinian order, which notes that Augustine “developed a rigorous puritanical attitude towards sexuality that [has fixated] European culture until the present day.” Almost 1600 years later there was reason for hope that Augustine’s influence would be overcome. Part 2 will explain how that hope was dashed.

Part 1 explained that Catholic teaching on contraception is part of the Church’s larger teaching on marriage. Both reflect the views of St. Augustine of Hippo (354-430 A.D.), who was influenced more by Manichean heresy than Christian tradition. This fact is well documented and is acknowledged by the Augustinian order, which notes that Augustine “developed a rigorous puritanical attitude towards sexuality that [has fixated] European culture until the present day.” Almost 1600 years later there was reason for hope that Augustine’s influence would be overcome. Part 2 will explain how that hope was dashed.

Fifty years ago, for a brief time, Catholics around the world anticipated that the Church might free itself from the Augustinian influence, adopt a more positive view of sexuality in marriage, and lift the ban on contraception. The occasion was the Second Vatican Council convened by Pope John XXIII in 1964. As part of the Council, John established a Papal Commission on Birth Control, which was expanded by his successor Paul VI several years later to include not only theologians but also members of the hierarchy, physicians, and lay people. Among the lay members were Pat and Patty Crowley, founders of the Christian Family Movement (CFM).

In Turning Point, Robert McClory tells the full story of the commission and of the Crowley’s’ role in it. There was much debating for and against changing the Church’s position on contraception. The contributions ranged from the scholarly to the experiential. For example, Father Bernard Häring argued that it was up to parents, rather than theologians, to “discern the will of God regarding parenthood within existing conditions and in an environment of love,” adding that it is not important that “every marital act be procreative, but that the marriage in its totality should be.” Patty Crowley quoted a CFM member’s testimony: “We do not believe that every time a man and wife feel a need to express their love to each other . . . it is a ‘call from God’ to raise more kids.”

Albert Görres, a German physician and psychology professor expressed disappointment that “one or two of the Holy Father’s private theologians” or ”a curial authority” have decided “questions of the greatest importance for life.” He went on to claim that a great deal of moral doctrine has been infected by Manichaeism, sexism, and false science, and that as a result, “moral theologians have justified with great confidence things that their successors today reject as outright immoral and unchristian: witch trials, tortures, burning of heretics, slavery, forceful violation of the consciences of unbelievers and heretics, suppression of colonial peoples, and . . . the castration of choirboys, this last over a period of centuries and with the approval of popes.”

Toward the end of the debates Dr. André Hellegers offered this conclusion: “The debates have convinced me more of the intrinsic danger in irreformable statements than in the intrinsic evil of contraception.”

After discussing various questions about contraception raised by the commission, nineteen theologians each made a six-minute presentation and then voted on two questions: Is the doctrine of Castii Connubii irreformable? And is artificial contraception an intrinsically evil violation of the natural law? The response to both questions was the same: four voted “yes,” and fifteen voted “no.” The majority report of the commission that was sent to the Holy Father mirrored the theologians’ conclusions and called for him to approve contraception for married couples.

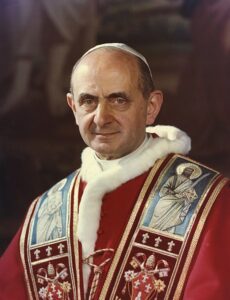

At that point, however, a powerful opponent of change, Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani, joined by Father John Ford and philosophy professor Germain Grisez, counseled Paul VI to reject the majority report and hold firm on the Church’s condemnation of contraception. Paul, who reportedly was already leaning toward their position, acceded to their request and wrote the encyclical Humanae Vitae supporting the position set forth in Casti Connubii.

Some commentators suggest that Paul VI’s decision was made solely out of fear of change or as a way to avoid calling papal infallibility into question. There may be some truth to that idea. But it is just as likely that there was another reason—Paul’s awareness that Judeo-Christian culture was at that very moment being challenged by Alfred Kinsey’s sex research (which would later be found fraudulent), Humanistic Psychology’s thinly veiled libertinism, and the popularization of both by Hugh Hefner and others. Paul may well have believed that any change in the Church’s teaching on marriage would be seen as an endorsement of those trends. But no matter the reason, Paul’s rejection of the Papal Commission on Birth Control’s advice on contraception widened the gap between the Church’s hierarchy and its theologians and laypeople.

Part 3 of this essay will discuss why the Catholic hierarchy have continued to remain silent about the division exacerbated by Humanae Vitae over half a century ago, and how the Church would benefit from breaking that silence.

Copyright © 2022 by Vincent Ryan Ruggiero. All rights reserved