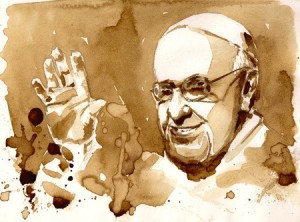

On the day before Palm Sunday 2018, young people in the U.S. participated in a march in favor of gun control. The following day, Pope Francis delivered a sermon at the Vatican encouraging young people to speak out on issues they feel strongly about. Though he has spoken in favor of gun control in the past, he did not mention it specifically in the sermon, so his advice was understood to be more general. Here is an excerpt:

On the day before Palm Sunday 2018, young people in the U.S. participated in a march in favor of gun control. The following day, Pope Francis delivered a sermon at the Vatican encouraging young people to speak out on issues they feel strongly about. Though he has spoken in favor of gun control in the past, he did not mention it specifically in the sermon, so his advice was understood to be more general. Here is an excerpt:

The temptation to silence young people has always existed . . . There are many ways to silence young people and make them invisible. … There are many ways to sedate them, to keep them from getting involved, to make their dreams flat and dreary, petty and plaintive . . . Dear young people, you have it in you to shout. It is up to you not to keep quiet. Even if others keep quiet, if we older people and leaders, some corrupt, keep quiet, if the whole world keeps quiet . . . I ask you: Will you cry out?

What should we make of Pope Francis’ sermon? We can begin by acknowledging that today’s young people need intellectual and moral guidance and no one is in a better position than the Pope to provide it. Furthermore, no fair-minded person would doubt his good intentions in doing so.

In addition, his assertion that many are tempted to “silence” and “sedate” young people, to keep them from involvement in important matters, and to stifle their dreams is not only true but also striking. I say “striking” because over the centuries the Church itself has struggled with the same temptation—as well as the companion temptation to silence older people—and in all candor has often succumbed to it. Even though Francis did not mention those facts, implying them underscores his humility.

Those positive aspects notwithstanding, Pope Francis’ message falls far short of the wise counsel he intended. For one thing, he does not acknowledge that protests are not always what they seem. They may be billed as one thing, yet be something very different. A demand for order and justice may instead be a means of sowing disorder and division. Crowds of well-meaning, concerned citizens can be transformed into a mindless mob shouting for actions with consequences beyond their imagining.

It has always been so—remember “Crucify him!” In our time, however, the methods of stirring up crowds have become vastly more sophisticated. There is today what economic analyst James Simpson has termed “the strategy of forcing political change through orchestrated crisis.”

Here is how such orchestration works. In a book he dedicated to “Lucifer,” community organizer Saul Alinsky advised young radicals to put aside confrontation and adopt an approach that masks their goal of social havoc. He wrote: “Tactics must begin within the experience of the middle class, accepting their aversion to rudeness, vulgarity, and conflict. Start them easy, don’t scare them off.” This approach, he explained, would facilitate “the radicalization of the middle class.”*

If modern culture emphasized emotional control and intellectual maturity, young people might be able to resist such tactics. But since the 1960s, our culture has been dominated by Humanistic Psychology, which claims that humans are born wonderful rather than flawed by Original Sin, and any shortcomings and failings they develop later are caused by their parents, teachers, and other authority figures. (Ironically, the Pope’s advice to young people seems to assume they have special insight or perception lacking in adults. He does not say—and assuredly would not say—that they are free from the stain of Original Sin, but at a time when Humanistic Psychology is still dominant, even a faint hint at that notion may offer false encouragement to those who deny the need for Redemption.)

The idea that adults alone bear the blame for shortcomings and failings is also responsible for the tendency among younger people to demonize great historical figures such as Christopher Columbus, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson. Even more importantly, the idea has encouraged them to value self-esteem over self-control and impulsiveness over restraint.

As a result of these emphases in western culture, young people are vulnerable to almost any movement—no matter how unreasonable or dangerous—that strokes their egos and flatters their preconceptions.

In light of these facts, I submit that Pope Francis’ Palm Sunday message was potentially dangerous to society in general and government and religion in particular. The enemies of democratic principles and Judeo-Christian beliefs and values are numerous, active, and better organized than ever. They have already gained a significant foothold in the entertainment and communications media, education, and government. Thus, encouraging young people to speak out on issues they feel strongly about, without any qualifying advice, increases their vulnerability to manipulation.

A better message for young people is this:

First, resist the temptation to speak or act on emotion alone, particularly concerning controversial matters. Instead, ask yourself why you feel as you do. Is it because of something you read in a book or essay, or heard others say; for example, news commentators, professors, or friends?

Next, put emotion aside and think about the issue, asking these questions: What evidence, if any, was offered in support of the view you read or heard? What view opposes the one you read or heard, and what evidence supports the opposing view? (If there are more than two opposing views, examine them all.)

Finally, evaluate the evidence and arguments on all sides of the issue and decide which view is most reasonable. In some cases, each side will be partly right and partly wrong, so the most reasonable view will be one that combines elements from both sides.

Moving beyond their feelings and proceeding in this thoughtful way will enable young people to avoid being victimized by selective reporting, emotional tricks, and the deception that Pope Francis himself has publicly denounced as “fake news.” It will also enable them to speak and act more meaningfully about controversial issues.

* Saul Alinsky, Rules for Radicals (NYC: Random House, 1971), pp. xvii, 3, 195.

Copyright © 2018 by Vincent Ryan Ruggiero. All rights reserved