It was the early 1990s and I had just finished a lecture to a group of educators on the teaching of critical thinking. Several people came up to the podium for further discussion. Though I’ve forgotten most of the exchanges, I remember one very well.

It was the early 1990s and I had just finished a lecture to a group of educators on the teaching of critical thinking. Several people came up to the podium for further discussion. Though I’ve forgotten most of the exchanges, I remember one very well.

A woman asked, “Do you know how many times you used the male pronoun versus the female pronoun?” I confessed that I didn’t. So she told me: “Eighty-eight versus seventeen” or some such set of figures. Then she delivered a short lecture of her own about how disappointed she was in me. Clearly, in her eyes I was, intentionally or otherwise, a sexist swine.

Dumbfounded, I asked if she had anything to say about the content of my talk. She didn’t. Her focus was singular—male versus female pronouns. Evidently, she had gathered a supply of pens and pads and traveled to the conference for the sole purpose of keeping a stroke tally of speakers’ offenses. (“It’s a tough job but somebody . . . .”)

Even in that benighted time, that woman had a lot of company, though not all of them were as mathematically inclined. Now that the country’s and most of the planet’s consciousness has been raised, the swine herd’s numbers have been reduced, and sentences like this are encountered everyday:

Everyone at the party put their coats in the guest room.

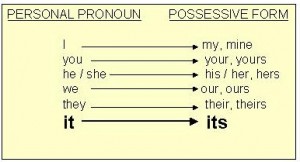

When such a sentence is uttered, people never rise up as one and shout “Arrrgh—you’ve mismatched your pronouns.” But they should. The rule is that “everyone,” “each,” “whoever” and similar words are singular and require the singular pronouns “he,” “she,” or “it”; “his,” “hers,” or “its”; “himself,” “herself,” or “itself.”

The rule is certainly not a new one. It has guided English expression for centuries. How many centuries, you ask? Here’s a passage from the prologue of the Canterbury Tales, written in the late 1300s and rendered here first in the original Middle English and then in modern English. Note the words in bold:

This is the poynt, to speken short and pleyn,

That ech of yow, to shorte with oure weye,

In this viage shal telle tales tweye

To Caunterbury-ward, I mene it so,

And homward he shal tellen othere two,

Of aventures that whilom han bifalle.

This is the point, to put it short and plain,

That each of you, beguiling the long day,

Shall tell two stories as you wend your way

To Canterbury town; and each of you

On coming home, shall tell another two,

All of adventures he has known befall.

If there is a skeptic among my readers, he or she (notice I didn’t say “they”) might think Chaucer used “he” because all the people in his fictional group were men. That was not the case. There were women, as well.

Presumably no one at that time or for centuries later was outraged that Chaucer did not write “each of you . . . they.” And people’s acceptance of his phrasing was not just because their collective consciousness had not yet been raised. No, it was because they valued the principle of consistency in pronoun use.

For those who also value fairness in gender reference, the good news is that there is are ways to honor this at the same time that you honor pronoun consistency. Instead of saying, “Everyone at the party put their coats in the guest room,” you can say:

Everyone at the party put his or her coat in the guest room.

or

Everyone at the party put his/her coat in the guest room.

or

All who attended the party put their coats in the guest room.

Of course, if only men were present, you could say “Everyone . . . his,” and if only women were present, “Everyone . . . her.” (Or, never a bad choice in this as in so many matters, remain silent.)

By following this simple advice, you will avoid the embarrassment I experienced at that long-ago conference, when I was stroke-tallied into awareness of my unconscious chauvinism.

Copyright © 2013 by Vincent Ryan Ruggiero