Three millennia ago, an astounding physical conflict took place in the Middle East. A giant Philistine named Goliath challenged a young Israel shepherd boy named David to battle. Goliath stood 9 feet 9 inches tall and was an experienced warrior. David was a young shepherd with no fighting skill and no weapon other than a sling and a few stones. Goliath was certain to win. Yet against all odds, David won and went on to become King of Israel. (1 Samuel 17:4f)

Three millennia ago, an astounding physical conflict took place in the Middle East. A giant Philistine named Goliath challenged a young Israel shepherd boy named David to battle. Goliath stood 9 feet 9 inches tall and was an experienced warrior. David was a young shepherd with no fighting skill and no weapon other than a sling and a few stones. Goliath was certain to win. Yet against all odds, David won and went on to become King of Israel. (1 Samuel 17:4f)

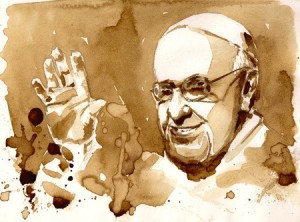

Three millennia later, in early 2025, an intellectual conflict took place in Western culture. Pope Francis, age 88, long a member of the prestigious Society of Jesus who held an advanced degree in moral theology, had taught that subject and written extensively on it, and had been in turn a bishop, an archbishop, a cardinal, and the anointed leader of the Roman Catholic Church, challenged a 40-year-old elected official’s view of a moral issue. Though the elected official, J.D.Vance, had an advanced degree in law, he was a convert to the Catholic Church and had no formal background in moral theology. No informed person could have doubted that Pope Francis would demonstrate his impressive wisdom and Vance’s ignorance. Yet the opposite happened. Vance’s view of the issue not only proved superior, but also raised significant questions about Catholic teaching.

Before looking at the details of the conflict, let’s examine some relevant background.

Background: Pope Francis has challenged the U.S. deportation of illegal migrants since the first Trump presidency when he declared that anyone who builds a wall to keep migrants out is “not a Christian,” and added that “the act of deporting people who in many cases have left their own land for reasons of extreme poverty, insecurity, exploitation, persecution or serious deterioration of the environment, damages the dignity of many men and women, and of entire families, and places them in a state of particular vulnerability and defenselessness” . . . What is built on the basis of force, and not on the truth about the equal dignity of every human being, begins badly and will end badly.”

The Conflict Between Vance and Pope Francis

Vance, the Layman defended the Trump administration’s deportation of illegals: “As an American leader, but also just as an American citizen, your compassion belongs first to your fellow citizens. It doesn’t mean you hate people from outside of your own borders . . . But there’s this old-school [concept] — and I think a very Christian concept, by the way—that you love your family, and then you love your neighbor, and then you love your community, and then you love your fellow citizens in your own country, and then after that you can focus and prioritize the rest of the world. A lot of the far left has completely inverted that. They seem to hate the citizens of their own country and care more about people outside their own borders. That is no way to run a society.” [Note: the concept Vance referred to and I have highlighted is historically known as ordo amoris.]

Francis, the Pontiff, challenged Vance’s view that family, neighbor, and fellow citizens take precedence over the rest of the world. Francis argued that “Christian love is not a concentric expansion of interests that little by little extend to other persons and groups . . .The true ordo amoris that must be promoted is that which we discover by meditating constantly on the parable of the ‘Good Samaritan,’ that is, by meditating on the love that builds a fraternity open to all, without exception.“

As would be expected, U.S. Catholic prelates supported their superior, Pope Francis, rather than Vance. (Judging by the bishops’ prior statements on the subject, that support was likely genuinely felt rather than a mere courtesy.)

Three Catholic theologians support Vance: Given theologians’ subordination to the Pope, it would be astounding if one of them publicly questioned his judgment on such a prominent issue as immigration. However, in this case at least three experts sided with Vance:

Dominican Father Pius Pietrzyk, a canon lawyer and a professor, told [Catholic News Agency] that the concept is a well-established one and is “evident both by revelation and reason.” He cited St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas in support of this judgment.”

Catholic philosopher Edward Feser stated that Vance’s position was “the correct view.” He explained further that “the view that one has the same duties to all human beings, rather than special duties to those closest, in no way reflects a conception of human beings as social animals . . . The correct view (common to Confucius, Aristotle, Aquinas, and the common sense of mankind in general) is that our social nature and its consequent obligations manifest themselves first and foremost in the family, then in local communities, then in the nation as a whole, and only after that in our relationship to mankind in general.”

Michael Sirilla, Franciscan University Professor of Philosophy, said “St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas express “ordo caritatis” (the order of charity) eloquently and Vance summarizes it here “deftly.”

The Significance of the Vance/Francis Outcome

People unfamiliar with Catholicism may think that the Vance/Francis disagreement is an interesting case with an unexpected outcome, but beyond that “no big deal.” That reaction is understandable. But for educated Catholics the outcome is very significant. The fact that a Catholic Pope is mistaken about one of the most important moral issues facing not only the U.S. but in fact the entire world, recalls several very relevant facts:

Prior to the year 1054, there were five patriarchs in the Catholic Church. They resided in Rome, Alexandria, Antioch, Constantinople, Jerusalem. The Patriarch of Rome was regarded as “first among equals,” but he had no authority over the other four. Then the Roman Pope asserted “universal jurisdiction and authority,” while the others believed the Church’s issues “should be decided by a council of bishops.” This break in the Catholic Church was known as the “Great Schism.”

The idea that the Patriarch of Rome held precedence was not new in 1054. Early in the fifth century St. Augustine had said “Rome has spoken; the cause is finished” (Latin, Roma locuta; causa finita est) and that expression has remained common in the Western Church ever since.

Various attempts have been made to heal the Great Schism (as well as the Protestant Reformation that occurred in the early 1500s), but a major barrier to doing so was created in the First Vatican Council of 1868 with the following proclamation:

“We teach and define as a divinely revealed dogma that when the Roman pontiff speaks EX CATHEDRA, that is, when, in the exercise of his office as shepherd and teacher of all Christians, in virtue of his supreme apostolic authority, he defines a doctrine concerning faith or morals to be held by the whole church, he possesses, by the divine assistance promised to him in blessed Peter, that infallibility which the divine Redeemer willed his church to enjoy in defining doctrine concerning faith or morals. Therefore, such definitions of the Roman pontiff are of themselves, and not by the consent of the church, irreformable. So then, should anyone, which God forbid, have the temerity to reject this definition of ours: let him be anathema.” [Chapter 4:9, Emphasis added]

The Questions Raised by Francis’ Error

Question 1: Does Francis’ error about the concept of ordo amoris articulated by both St. Augustine and St. Thomas challenge the doctrine of Papal Infallibility?

The Vatican would say no, not at all. They would explain that the conditions surrounding “Ex Cathedra” pronouncements are so precise and limiting that they are exceptionally rare, and this case does not meet those conditions. However, that answer seems more evasive than persuasive. The present matter of immigration is certainly a moral issue—indeed, a universal and serious issue involving billions of people in innumerable countries. And the language Francis uses to assert his view on immigration allows no room for disagreement. In fact, it fits the words Vatican II used to describe a infallible statement; that is, one that “defines a doctrine concerning faith or morals to be held by the whole church,” and says such a doctrine is “irreformable.”

Moreover, as noted earlier, prior to the exchange with Vance, Francis had said that “anyone who builds a wall to keep migrants out is “not a Christian.” And in the exchange with Vance Francis said, “The true ordo amoris” “must be promoted,” and is “part of a love that builds a fraternity open to all, without exception.” [Emphasis added] Whether Francis meant to be speaking infallibly may be debatable. But it is fair to say he should have understood that millions would assume that he meant his statement to be so. And he should have realized that his careless error about ordo amoris would call into question the doctrine of Papal infallibility.

Question 2: Does Francis’ error concerning ordo amoris call into question the Church’s position on the Great Schism of 1054? In other words, was the idea that the Roman Pope deserved elevation over the other Patriarchs really sounder than their position that Church’s issues “should be decided by a council of bishops”?

This question is impossible to answer definitively. Nevertheless, it is not unreasonable to believe that the Protestant Reformation would likely have been avoided if the Patriarchs’ position had been embraced centuries earlier. Accordingly, that centuries later Vatican II’s pronouncement on the matter of Papal infallibility may not have been made, and that the Church’s present view of immigration might, at very least, have been preceded by a broader, more penetrating consideration of the effect of open borders on the world.

Question 3: Does Francis’ error about ordo amoris cause confusion about the guidance of the Holy Spirit? In effect, yes. But since confusion already existed, it would be more accurate to say his error dramatically increased confusion.

Consider Francis’ own view about such guidance. In 2013, he said this: “The Holy Spirit, then, as Jesus promises, guides us ‘into all truth‘ . . . [and] leads us not only to an encounter with Jesus, the fullness of Truth, but guides us ‘into’ the Truth . . . helps us enter into a deeper communion with Jesus himself, gifting us knowledge of the things of God. . . The Tradition of the Church affirms that the Spirit of truth acts in our hearts, provoking that ‘sense of faith,’ . . . penetrates it more deeply with right thinking, and applies it more fully . . . Let’s ask ourselves: are we open to the Holy Spirit, do I pray to him to enlighten me, to make me more sensitive to the things of God?” [Emphasis added]

Note that Francis acknowledges that the Holy Spirit speaks not just to the Pope nor to the hierarchy in general, but to all of us, and confirms that this is consistent with traditional Catholic teaching.

So where exactly is the confusion? In the tension between the two teachings: On the one hand, the Holy Spirit speaks to all of us. On the other hand, only the Pope receives infallible messages that cannot be false and must therefore be accepted under pain of excommunication. I say “tension” because the idea that some of the Holy Spirit’s messages could be false is implied but not stated. The only circumstance that could elevate the “tension” to full-blown contradiction would be for the Pope to express a false view as true. And Francis has done precisely that in his advocation of open borders. As a result, the confusion in the Church has been dramatically increased.

Question 4: Are there other negative effects to Francis’ mistaken view of open borders than confusion. Definitely, and they are serious.

Politicians in the U.S. and other countries who reject the rule of law and other principles of civilized government have been encouraged to promote anarchy. Bishops have become so busy shepherding other countries’ flocks that they have ignored their own. They have also refused to question “woke” social policies that foster rather than attack injustice, and demanded that their parish priests do the same. Catholic citizens have thus been denied the leadership in discernment needed to distinguish good from evil and virtue from vice.

Question 5: How can Catholics who recognize Francis’ error and the negative consequences explained above avoid losing their faith in their Church and the guidance of the Holy Spirit?

First, in times of confusion and disappointment we need more than ever to be closer to Jesus, so we should keep attending Mass and receiving the Eucharist.

However, equally important, the errors of the Church hierarchy require us to be more cautious in receiving their guidance. Doing so is not disrespectful but merely prudent. In other words, we need to depend more on ourselves than on the Church hierarchy in separating truth from falsehood, wisdom from foolishness. (With modern news reports frequently being biased, anyone, including prelates, can be misinformed.) Thankfully, one of God’s great gifts to us is our minds. We need only be diligent and focused in our use of them.

One way to make better use of our minds is to add a new form of prayer to our usual prayers. The new prayer begins by calling to mind a problem or issue, or simply an idea we have we have encountered in the news, from friends or acquaintances, or in messages from pastors, bishops, or the Pope. Next, we ask the Holy Spirit for guidance in solving the problem or issue or evaluating the idea. Then we remain silent. If thoughts even remotely related to the subject come, we ponder them; if unrelated thoughts occur, we ignore them. We mustn’t be disappointed if we hear or sense nothing at that time, or the next time, or the tenth time we seek the insight. If we are patient and trust, the habit of opening our mind to the Holy Spirit will be rewarded.

The guidance we receive may take any number of forms—a word or phrase to look up in a thesaurus, a memory related to our quest, a quotation, even a song lyric. It may come when least expected, such as in the middle of the night. And it will frequently warrant further search on our part. For example, if Lord Acton’s sentence “Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely” comes to mind, we might reconsider the trustworthiness of our news sources. And if Jesus’ words “By their fruits will you know them” come to mind, we might resolve to determine the possible consequences of political programs before supporting them. .

One final way to maintain our faith is to rethink our conception of our Bishops and our Pope. Many of us have been taught, or at least given the impression, that anointment has made them spiritually superior beings filled with divine insights. That conception has been as unhealthy for them as for the rest of us. It would be much better to see them as we see the rest of humankind, as imperfect beings prone to sin and error, striving to grasp the truth but often failing, but with the added temptation of believing in their superiority and thereby losing the saving grace of humility. Seeing them this way will make it easier to balance our anger at their arrogance with sympathy for their difficult responsibilities, to pray for them, and most importantly, to forgive them with the same generosity we hope to receive.