My subject, however, is not those events but the experience of another Jewish man over nineteen hundred years removed from the time of Jesus. His name was Viktor Frankl and his life and work have enriched many people’s understanding of the Christian faith.

At first consideration, my topic may seem odd for Holy Week because Frankl never publicly embraced Christianity nor wrote anything directly supportive of its teachings. But what he did was illuminate a matter intimately related to Christianity and religious faith in general—what it means to be human—and he did so at a time when millions of people had lost that understanding.

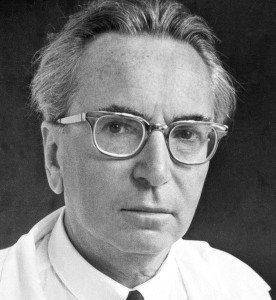

Viktor Frankl was a learned man, with advanced degrees in both medicine and philosophy. As a young psychiatrist, he was associated with the two giants of his field, Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler. The former claimed that sex is the fundamental drive in humans; the latter claimed that it is power. Frankl eventually proved both those views wrong. And the way he did so—by personally experiencing the horror of Hitler’s concentration camps—was reminiscent of Jesus’ via dolorosa.

Frankl realized that something terrible was on the horizon for European Jews in the 1930s, and he had prepared to leave his native Austria with his wife. But concern for the safety of his parents gave him pause. One day, he noticed a piece of marble his father had picked up from what was left of the synagogue after the Nazis had destroyed it. His father explained the marble was from a slab that had the Ten Commandments engraved; specifically, from a piece that contained the command to honor one’s father and mother.

Frankl interpreted the piece of marble as a sign and decided to stay with his parents. Before long, his parents, wife, sister, and he himself were arrested and sent to Auschwitz. (All but Frankl and his sister perished.)

Like his fellow inmates, Frankl experienced shock, disbelief, and a kind of emotional death. But he also witnessed heroism and nobility. For example, he tells the story of how a starving inmate stole some potatoes from the storehouse. The camp officers learned of the theft and told the inmates they could either give up the guilty man or give up their own food for a day. Though the culprit was known, 2500 men chose to give up their food to protect him.

Far from what Freud might have expected, there was in the camps almost no concern about sex, even in dreams. Yet there was notable interest in politics and even more in religion, and the latter was both deep and sincere. In fact, “the depth and vigor of religious belief often surprised and moved a new arrival.” The attitude of most inmates was also surprisingly positive. As Frankl explains, “it did not really matter what we expected from life, but rather what life expected from us.”

Frankl details the concentration camp experience and its lessons about life in the deeply moving book, Man’s Search for Meaning. The fundamental human drive, he explains, is the drive to find meaning in life, and that can be accomplished in any of three ways: to create a work or perform a deed, to experience something through one’s labor or encounter someone through love, or to suffer well. Of the latter way, he comments, “When we are no longer able to change a situation [such as in the case of] inoperable cancer—we are challenged to change ourselves.”

In the midst of his own suffering, Frankl explains, he “grasped the meaning of the secret that human poetry and human thought and belief have to impart: the salvation of man is through love and in love.”

Frankl developed the form of therapy he called logotherapy (that is, “meaning” therapy). Here is an example of this therapy in Frankl’s own words:

“Once, an elderly general practitioner consulted me because of his severe depression. He could not overcome the loss of his wife who had died two years before and whom he had loved above all else. Now how could I help him? What should I tell him? I refrained from telling him anything, but instead confronted him with a question, ‘What would have happened, Doctor, if you had died first, and your wife would have had to survive you?’ ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘for her this would have been terrible; how she would have suffered!’ Whereupon I replied, ‘You see, Doctor, such a suffering has been spared her, and it is you who have spared her this suffering; but now, you have to pay for it by surviving and mourning her.’ He said no word but shook my hand and calmly left the office.”

Frankl wrote many books before he died in 1997, but my favorite is Man’s Search for Meaning. In it he demonstrates that the importance of love and the value of suffering are confirmed by scientific reasoning as well as by faith. His message provides a bulwark against the view that religious values are outmoded or utopian. It also helps us to appreciate more fully the life and teachings of our Lord and the meaning of His death and resurrection.

Copyright © 2013 by Vincent Ryan Ruggiero. All rights reserved