This essay is the sixth in the series “Good Habits.” The discussion is based on my book of the same title.

This essay is the sixth in the series “Good Habits.” The discussion is based on my book of the same title.

Many people today seem to think moral character is something we have or don’t have, and nothing can be done to acquire it. That idea is mistaken. Many others believe that having moral character simply consists of knowing right from wrong. That is also mistaken. We can know right from wrong and yet rob, rape, and even murder.

Having moral character means not only knowing right from wrong but putting that knowledge to use in our lives, in other works doing good and avoiding evil, and that is a matter of developing moral habits.

The first step in developing moral character is to develop your conscience—that is, your “inner voice that distinguishes right from wrong. You may have had one in your youth but have since learned to stifle its messages to you. There are many levels of sensitivity to conscience. Some people can avoid stealing but not lying, or faithfulness to their spouse but not honesty with their employer.

How is conscience recovered or developed? By opening your mind to understanding what behavior is moral and what is immoral. Doing this is much easier if you have a religion than if you do not, because religions offer information about what pleases or displeases God. (Philosophy offers similar, but less abundant insights into right and wrong.)

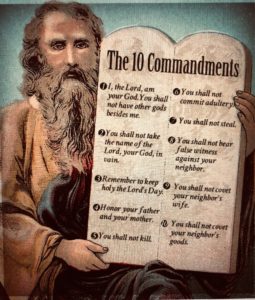

Christians and Jews depend on the Bible for such insights, most notably in the Ten Commandments. Also, in passages like these: “Blessed are the Gentle . . . Blessed are the merciful . . . Blessed are the peacemakers” (and more) in Matthew 5:3-11. Also, “Love your enemies. . . treat others as you wish to be treated” (and more) in Luke 6:24-42.

The second step in developing moral character is identifying your own moral offenses. The Judeo-Christian perspective on the matter is nicely summed up in a Russian proverb, “Make peace with [other people] and quarrel with your faults.” Your aim is not to hate yourself but to hate your past offenses and motivate yourself to avoid them in the future. Though easy to say, this is not easy to do. It requires being honest with yourself and getting beyond “It wasn’t my fault,” “I couldn’t help it,” and “It really wasn’t THAT bad.”

It can be difficult to identify your moral offenses. (Identifying other people’s is for some reason much easier.) If you have such difficulty, consider the obligations you have to others. For example, to a spouse, children, sibling. Also, consider the “seven deadly sins,” which represent a broad category of offenses. They are pride, covetousness, lust, anger, gluttony, envy, and sloth. Yet another approach is to consider moral ideals to strive for, including justice, fairness, tolerance, compassion, loyalty, forgiveness, harmony, and mutual understanding. All these approaches can help you determine your moral strengths and weaknesses and be alert to temptations to immorality.

The third step in developing moral character is to develop a strategy for improving your behavior. For example, if you tend to be suspicious of others, make a special effort to resist that tendency and instead give others the benefit of the doubt. Or if you at tempted to gossip about others, develop the habit of speaking well of others whenever possible.

These steps to becoming a better human being can be summed up as striving to be a “Gentleperson.” This can be difficult if you have been taught to “look out for number one.” But it is well worth the effort to change. Being a “Gentleperson” doesn’t mean being spineless or silent on matters of principle. It means, instead, applying the Golden Rule in your relations with others by avoiding confrontations and meeting rudeness with civility, impatience with patience, meanness with kindness. I know of no better way of expressing this way of living than the following prayer mistakenly attributed to St. Francis of Assisi but reflective of his life’s example:

Lord, make me an instrument of your peace

Where there is hatred, let me sow love;

Where there is injury, pardon;

Where there is doubt, faith;

Where there is despair, hope;

Where there is darkness, light;

Where there is sadness, joy;

O Divine Master, grant that I may not so much seek

to be consoled as to console,

to be understood as to understand,

to be loved as to love.

For it is in giving that we receive,

it is in pardoning that we are pardoned,

and it is in dying that we are born to eternal life.

Copyright © 2025 By Vincent Ryan Ruggiero. All rights reserved.