The comedian Red Skelton created a character called “The Mean Kid,” who would say “If I dood it I get a whippin’,” (If I do it, I’ll get a whipping). Then he would think for a moment and declare, “I dood it” (I’ll do it). It always got a laugh because everyone in the audience had experienced realizing an action is wrong and then doing it anyway.

In Catholic theology, that behavior is known as committing a sin and is considered the result of a flawed nature and a weakened will. The condition is not limited to one ethnic or age group or to one gender. All humans are cursed with it, however pleasant it may be to believe ourselves exempted.

The Ten Commandments categorize the sins to which we are tempted, and Scripture provides voluminous examples of inadequate resistance to temptation. Sexual sins include men raping women—see for example, Amnon and his sister Tamar (2 Samuel 13) and Schechem and Dinah (Genesis 34). Also, men seducing women and women seducing men. See Potiphar’s wife and Joseph (Genesis 39), Samson and Delilah (Judges 16), and David and Bathsheba (2 Samuel 11). Unfortunately for sinners, one of the Commandments condemns the most common way of hiding such sins—lying about them.

Scripture informs us that the antidote to sin is God’s grace and it is readily available. Yet we are as free to reject grace as to ignore insights from hard-won human experience. Here are a few of those insights:

Temptation can arise suddenly and prompt us to behavior we would not otherwise engage in, even behavior we have strongly resolved to avoid.

Overindulgence in alcohol or drugs increases our vulnerability to temptation and can make resistance considerably more difficult.

Acts performed when inebriated may be blocked from memory.

A therapist’s aid in recovering a blocked memory can significantly alter the memory without the person’s realization.

An altered memory will seem as true as an unaltered memory, and if it is more pleasant, we will also want it to be true.

Regret or shame over something we have done (while inebriated or sober) can lead us to deny that the act ever happened, or to transfer responsibility to someone else.

Even when we are aware at the outset that our denial or change of details is not truthful, as is sometimes the case, if we repeat the false version often enough, our confidence in it will grow. And if we also hear it repeated by others—for example, by our supporters and in newscasts—we will regard it as a certainty.

Many of these insights into human behavior are ancient, and psychological research has confirmed them over the last century or so, ironically at the very time when the Catholic view of sin was being consigned to the trash heap of outmoded ideas.

In recent decades the insights, too, have been added to the trash heap on the theory that any admission of imperfection (let alone sin) undermines our self-esteem and compromises our mental health and therefore cannot be tolerated.

This discarding has been most unfortunate. The insights mentioned above help us maintain the humility to say our recollection of an event might be mistaken. That is no small thing. It enables us to open our minds to the evidence that could settle the issue. Without it, we have no motivation to seek the truth.

The modern rejection of the idea of sin, of the belief that human beings are inherently imperfect, and of the related insights into human behavior noted above has not only compromised our assessment of our personal faults and mistakes. It has also undermined the traditional way of making ethical and legal judgments. Conflicting narratives and testimonies used to be reconciled objectively—first by identifying and examining the evidence and then determining which story it supported. Today the process has become subjective—ignoring evidence, simply noting which narrative or testimony fits our presuppositions, and calling it the truth.

The clash between the old and new methods of reconciling conflicting testimony was on clear display during the Senate’s deliberations over Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court. The focus quickly became, not Kavanaugh’s lengthy judicial record, but instead on an incident of sexual abuse that allegedly occurred decades earlier. Professor Ford made the allegation; Judge Kavanaugh denied it. Democrat senators argued in the hearings and in press releases that Ford should be believed because women don’t lie about such serious matters, a subjective claim that ignored biblical testimony and scientific insights into the human problems with memory noted above. Republican senators noted that Ford’s story was not corroborated by the very witnesses she claimed would do so and that her story was vague about important details. Because of this, they argued, it did not meet the burden of proof, thus Kavanaugh’s presumption of innocence was not overcome.

In the end, the traditional way of reconciling testimony won the argument and Kavanaugh was confirmed. But the vote was very close. In other words, the Democrats’ shameless willingness to ignore more than two millennia of insight into human nature and the legal concept of innocent-until-proven-guilty almost succeeded in undermining American jurisprudence.

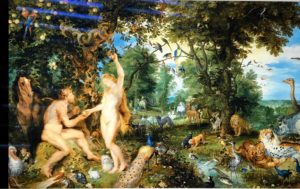

Although the Kavanaugh matter is closed, the movement toward social change it illustrated lives on. We should expect that movement to grow stronger and do serious mischief until modern culture once again acknowledges the echoes from the Garden and embraces biblical and scholarly wisdom.

Copyright © 2018 by Vincent Ryan Ruggiero. All rights reserved