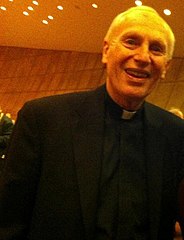

In a court deposition, Bishop Emeritus Howard J. Hubbard, Diocese of Albany NY, has admitted that when he received reports that eleven of his priests had sexually assaulted children, he neither notified the police, nor informed the laity, nor prevented the priests from serving in other dioceses. (Hubbard himself was accused of sex abuse, but claimed innocence.) Moreover, he reportedly placed all information about the abuses in a locked room to which only high level Church leaders had access.

This is certainly not the first time a Catholic bishop seems to have acted irresponsibly in such matters. Indeed, the list of similar cases is long and even includes that of Pope Benedict XVI.

In his deposition however, Hubbard offers clues about his rationale for covering up the sex abuse in the diocese he was in charge of for 37 years, in particular concerning the most egregious case, that of Father David Bentley. And those clues enable us to understand and evaluate what he and presumably other bishops were thinking in the sex abuse scandal. Here are some revealing parts of the 1143 page deposition:

When Hubbard first heard of the complaint against Bentley, he met with him and Bentley admitted that he was guilty of sexually assaulting the young man. Hubbard referred Bentley for treatment but did not reach out to the young man or his family because, he stated, Social Services was “providing assistance” to them. Nor did he report his meeting with Bentley to the police. Why not? Because, in his words, he was not a “mandated reporter,” adding “I don’t think the law then or even now requires me to do it.”

The deposer then asked Hubbard whether “Canon Law required [him] as a Bishop to keep secret anything that would be scandalous.” Hubbard said he did not believe there was such an obligation. He then explained that he had sent Bentley for treatment of his problem but kept the matter secret because of “[the danger of] scandal and respect for the priesthood.”

Later in the deposition Hubbard acknowledged that he and his peers in the magisterium had made some mistakes is their handling of priests involved in sexual abuse but he attributed the mistakes to not understanding that sexual abuse is addictive and tends to recur. Nevertheless, he stated that his choice to remain silent had been made “in the best interest of the church.”

These statements, made under oath, reveal several disturbing thought patterns:

1) His testimony focused only on LEGAL obligations, with no mention of his MORAL obligations, a most peculiar omission for any “man of the cloth,” let alone a Catholic bishop.

2) He suggested that only certain people—the “mandated” (whatever that means)—are required to report felonious behavior to the police. What a shallow notion. In reality, anyone who has such knowledge yet does not report it is, by that failure, complicit in the behavior. (Knowledge received under the seal of confession is, of course, exempt; but Hubbard’s testimony did not claim the seal was involved.)

3) He contradicted himself about the obligation to report priests’ crimes. First he said that he believes Canon law does not require being silent to avoid scandal, and then claimed he kept silent in order to avoid “the danger of scandal.” He then added a second reason for his silence, “respect for the priesthood,” but does not explain how reporting a criminal priest would be disrespectful of the priesthood. If anything, it would be a sign of respect.

4) In his further claim of remaining silent about sexual abuse in order to avoid scandal, Hubbard claimed he was acting “in the best interest of the church.” This wording is significant because it reveals his fundamental misunderstanding of a central concept in the Catholic faith—“church.” In Modern Catholic Dictionary, Fr. John Hardon explains the meaning of the term: “Since the Council of Trent, the Catholic Church has been defined as a union of human beings who are united by the profession of the same Christian faith, and by participation of and in the same sacraments under the direction of their lawful pastors, especially of the one representative of Christ on earth, the Bishop of Rome.” He underscores the centrality of people in the definition with these words: “As the community of believers, the Church is the assembly of all who believe in Jesus Christ . . . the People of God.”

When Hubbard said his silence was “in the best interest of the church,” he could not have been thinking of “the church” as human beings, believers, people of God. It was surely not “in the best interest” of the “people of God” to deny them knowledge of evils that mocked their faith and threatened their children. No, he was more likely thinking of “the church” as ceremonies and traditions or simply as the powerful association known as the Magisterium.

It would be unfair to ascribe Hubbard’s shallow thinking habits to all Catholic bishops. But on the other hand, given the number of dioceses in which pedophilia was ignored and offending priests moved to other parishes rather than being reported to the police, it would be naïve to believe Hubbard’s case is an insolated example.

Jesus said, “Let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them, for the kingdom of heaven belongs to such as these.” (Matt 19:14). He also warned that “whoever causes one of these little ones who believe in Me to sin, it is better for him that a heavy millstone be hung around his neck, and that he be drowned in the depths of the sea.” (Matt 18:6) These admonitions explain why Catholics were outraged to learn that those responsible for leading children to Christ were sexually abusing them, and even more outraged that bishops were silent about the offenses, and in some cases enabled them to continue their abuse in other parishes.

Bishop Hubbard’s deposition adds a dimension to the disappointment of Catholics with their bishops. For it suggests that in many cases the bishops’ failure to deal appropriately with pedophilia was caused not only by a lack of awareness or resolve, but also by a serious inadequacy in the prelates’ intellectual processes. To be more specific, by their failure to identify relevant scriptural insights and theological principles and choose actions consistent with them.

Whether this shortcoming requires the re-education of prelates is difficult to say, but there is no question that the laity’s trust in them will depend on whether they overcome the shortcoming.

Copyright © 2022 by Vincent Ryan Ruggiero. All rights reserved