Over the centuries Catholics’ regard for Mary has sometimes verged on worship. Although mainly true of the uneducated, excessive veneration of Mary has also occurred among educated Catholics, notably in the idea that Mary is Co-Redemptrix. This concept has existed since the early Christian Church, and has had both supporters and opponents in the Christian community. Today most Catholics agree with their fellow Christians that, though Mary deserves great respect, there is only one Redeemer: Jesus.

Over the centuries Catholics’ regard for Mary has sometimes verged on worship. Although mainly true of the uneducated, excessive veneration of Mary has also occurred among educated Catholics, notably in the idea that Mary is Co-Redemptrix. This concept has existed since the early Christian Church, and has had both supporters and opponents in the Christian community. Today most Catholics agree with their fellow Christians that, though Mary deserves great respect, there is only one Redeemer: Jesus.

It is unlikely that Catholics who have slipped from veneration to adoration of Mary intended to commit the sin of idolatry proscribed in the First Commandment, but they certainly seemed to do so. It is equally unlikely that Protestants who reacted by distancing themselves from Mary meant to disrespect her, but they certainly seemed to do so.

The question that both Catholics and Protestants would do well to ask is, “What place should Mary hold in Christian belief?”

Scripture says very little of Mary. Although all four Gospels and Acts mention her, the total number of references is only 21, most of them in Luke and Matthew, of which 16 concern the birth and infancy of Jesus. Yet despite so few scriptural references to Mary, we can draw a number of clear inferences from them.

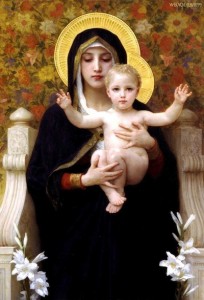

Mary carried the Son of God in her womb, shared her blood with Him. Hers was the first voice He heard, the first face He beheld. She provided His first lessons in speaking, in praying, in forming relationships with people, and in living by God’s commandments. (Some readers may be reluctant to acknowledge that Mary taught Jesus to pray and observe the commandments because they believe that, as the Son of God, He needed no instruction. But that view denies the historic Christian teaching that Jesus was ‘fully man and fully God.’ Although there is no way for logic to penetrate that mystery, we can be sure that in the sense that He was fully man, He needed instruction. Luke 2:52 seems to confirm this view, noting that as a boy, Jesus “kept increasing in wisdom and stature.”)

Moreover, Mary was with Jesus ten times longer than the Apostles were. Through all those years she prepared His meals, mended His garments, cared for Him when He was ill. Most importantly, she talked with Him, exchanged ideas with Him, and was His closest confidant. It is amazing that there has been little if any curiosity shown about this fact in the millions of words that have been written about Mary and Jesus. What exactly did Jesus and Mary discuss? What did Jesus share with her about God, our human history and nature, the meaning of life and death, His mission among us?

Although we cannot know the answers to such questions, we can certainly say this much: Mary knew Jesus as no one else, save the Father, knew Him. Moreover, Scripture tells us she “treasured” this knowledge in her heart (Luke 2:51). As Jesus’ mother, Mary also loved Him more than anyone other human being loved Him. And she shared His suffering on the cross as only a mother could.

Scripture also has little to say about what Jesus thought of his mother. Theology tells us that, as the Son of the Father, He loved her as He loves all humanity. But how did He love her as a man? We know Jesus’ love began in obedience to Mary and to Joseph (Luke 2:51). We also know His love went far beyond that, as evidenced by the events at the wedding at Cana (John 2:1-11.) When the wine ran out, Mary said to Jesus, “They have no wine.” He responded, “My hour is not yet come.” She did not answer Him, but said to the servants “Whatever he says to you, do it.” And Jesus proceeded to perform his first public miracle.

The brevity and subtlety of that passage hides its profundity. Mary must have known Jesus could perform miracles; otherwise she wouldn’t have mentioned that the wine had run out. (Interesting questions: How did she know He could perform miracles? Had He explained that to her before? Had she seen Him perform miracles in private?) She also must have been confident that He would honor her request; otherwise she would not have given instructions to the servants. More significantly, Jesus performed the miracle even though His “hour had not yet come.” So great was His love for her that He changed the divine timetable to honor her request!

Jesus further revealed His love for Mary when He suffered on the cross. Even in the midst of his agony, His thoughts were of her. Toward the end of the ordeal, looking down, He said to her “Woman, behold your son [referring to John].” Then He turned to John and said, “Behold your mother.” (John 19:26-27.)

We have been conditioned to think of great love stories as between a man and his wife, but this, the greatest of all love stories, was between the Son of God and His mother.

We can also infer from Scripture that Mary was the source of significant material in the gospels. For example, who told Luke about the angel Gabriel’s visit to Mary at the annunciation, the birth of Jesus, Mary’s visit to Elizabeth, Elizabeth’s greeting, and Mary’s response (the Magnificat), the presentation of Jesus in the Temple and the words spoken by Simeon and Anna? Scholars generally agree that Luke heard all these stories directly from Mary.

And who told John about the miracle at Cana? He was likely present at the wedding but probably not close enough to have heard the exact exchange between Jesus and Mary. The obvious answer is, Mary told him what was said. We need not ask how John knew of Jesus’ words to Mary from the cross because John was there and Jesus spoke to him as well. According to scholarly tradition, John followed Jesus’ direction and took Mary in to his home for many years and treated her as his mother. During that period they surely spent countless hours talking about Jesus.

It is possible that when Jesus said to John, “Behold your mother,” He was speaking solely to John. But Catholics have always believed that He was also speaking to all of us and asking us to take Mary into our hearts as John took her into his home. Some Protestants would say that interpretation stretches the meaning of the passage. However, it helps to explain John’s reference in Revelation 12:1-6 to the “woman clothed with the sun, and on her head a crown of twelve stars,” the one who “gave birth to a son, a male child, who is to rule all the nations . . . .” Who else could John have been referring to but the woman his Savior told him to regard as his mother? Who but Mary fits John’s description?

Protestants and Catholics have not always been so far apart in their view of Mary. For example, though the early Protestant reformers Wycliffe, Luther, and Zwingli rejected what they believed were Catholic excesses about Mary, they nevertheless honored her. Surely some of the present division is due to a misunderstanding of Catholic teaching.

Praying to Mary. The reason Catholics pray to Mary (and other saints) can be traced to the term “communion of saints,” which is found in the earliest Christian creed, the Apostle’s Creed. The term refers to the spiritual relationship that exists among the faithful on earth, the souls in purgatory, and the saints in heaven. (See, for example, 1 John 1: 1-4.) Further support for the belief in this “communion” is the reasoning, dating from the early Church, that just as God hears our prayers for one another, he hears the prayers of the saints for us. The most common prayer to Mary is scripturally based and asks only that she pray for us:

Hail Mary, full of grace,

The Lord is with thee. [See Luke 1:26]

Blessed art thou among women

And blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus. [See Luke 1:42]

Holy Mary, mother of God, [See Council of Ephesus, 431 a.d.]

Pray for us sinners

Now and at the hour of our death.

Amen

The Immaculate Conception. This belief (often confused with the virgin birth) is that God kept Mary free from original sin from the moment of her own conception. In other words, she had from that moment the grace others receive in Baptism. The idea behind this is that God would want as special a tabernacle for His Son Jesus as the tabernacle He specified for the Ten Commandments in Exodus 25:10-22.

The English Protestant poet William Wordsworth was referring to the Immaculate Conception when he famously described Mary as “Woman! Above all women glorified,/ Our tainted nature’s solitary boast.”

The Assumption. This belief holds that when Mary died (or before she died), she was transported directly to Heaven, body and soul. It was first recorded as a Christian belief in the fourth century a.d., but was not declared Catholic dogma until the 20th century. There is no clear, direct scriptural foundation for this belief. It is based, rather, upon tradition and on similar reasoning to that supporting the Immaculate Conception—in other words, that just as God created special conditions for Mary’s entering the world, he created special conditions for her leaving it.

Nothing about praying to Mary or believing in the Immaculate Conception and the Assumption can reasonably be construed as diverting attention from God the father or Jesus, or as undermining the Christian faith. Instead both the prayer and the beliefs are testimonies to God’s glory. Protestants may choose not to join in those testimonies, but they should respect them. And Protestants and Catholics alike should be able to affirm American Unitarian poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s tribute to Mary:

And if our faith had given us nothing more

Than this example of all womanhood,

So mild, so merciful, so strong, so good,

So patient, peaceful, loyal, loving, pure,

This were enough to prove it higher and truer

Than all the creeds the world had known before.

Of course, as Longfellow understood, our faith has given us much more. Nevertheless, his words serve as a reminder that God Himself chose Mary to be the mother of His only begotten Son; that He made her, as the gospel tells us, “full of grace” and “blessed among women”; and that, for these reasons, when Christians hold her in high regard, they are expressing gratitude and honor to their Creator.

Copyright © 2012 by Vincent Ryan Ruggiero. All rights reserved