From all indications, more and more Americans are experiencing disillusionment, despair, and even suicidal thoughts over the continuing decline of our culture. Such feelings are likely to be strongest among younger people who have grown up believing that having things go well is their birthright, and when things do not go well, that they have been victimized. Given that perspective, they spend considerable time searching for villains to hate, demonize, and lash out against. Their negative feelings toward those people are often so intense that they are incapable of forgiveness and tolerance. And many educators, journalists, and politicians—including those who nurtured the unreasonable expectations—are more than happy to point the finger of blame at parents, religious leaders, people in the opposition party, and the founders of the country.

Most of us understand that there’s something seriously wrong with this state of affairs. And all but the youngest among us also remember a time when it wasn’t this way, when despite strong differences and disagreements there was a basic foundation of genuine tolerance, mutual respect, and forbearance, and because of this a significant measure of social harmony. Those who remember not only miss that time. They are also eager to learn how to regain what made it satisfying.

It is widely assumed that the way to restore social harmony is to make changes in the culture, and that is true. But a necessary first step is to restore harmony within ourselves.

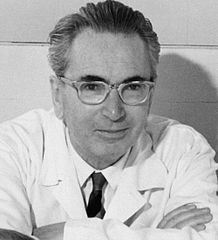

One way to achieve internal harmony was suggested by a brilliant observer of humanity in a slender volume published posthumously and titled Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything. That man was Viktor Frankl (1905-1997). He held advanced degrees in both medicine and philosophy. He was also a survivor of Hitler’s concentration camps, and the author of many books, notably Man’s Search for Meaning, whose relevance to our time I discussed in an earlier essay.

Yes to Life* is a compilation of lectures Frankl delivered in 1946, less than a year after his liberation from the concentration camp. He foreshadowed the themes that would follow by quoting this poem by Rabindranath Tagore: “I slept and dreamt that life was joy. I awoke and found that life is duty. I worked—and behold, duty was joy.” We need only pause and ponder that brief poem to realize that Frankl’s message may be even more relevant today than it was in his time.

Frankl says the most important question we can ask about life is not “What can I expect from life?” but instead “What does life expect from me?” In other words, “What task in life is waiting for me?” He explains further, “Life itself means being questioned . . . and answering; each person must be responsible for their existence. Life . . . is [thus] a task at every moment.” He then quotes C.F. Hebbel’s startling way of defining life— “Life is not something; it is the opportunity for something!” (Emphasis added)

“It is terrible,” Frankl noted, “to know that at every moment I bear responsibility for the next [moment]; that every decision, from the smallest to the largest, is a decision ‘for all eternity’; that in every moment I can actualize [its] possibility . . . or forfeit it. . . But it is wonderful to know that the future—my own future and with it the future of the things, [and] the people around me—is somehow, albeit to a very small extent, dependent on my decisions . . ..” He adds that what those decisions “bring into the world” becomes a reality that will remain forever.

Frankl clearly believed that life is not a matter of our being here and then gone, leaving only an empty space behind us. It is a matter of crafting a legacy, which can be wonderful or awful, depending on our responses to the challenges life poses for us. His message is all about doing good and avoiding evil, acting wisely, nobly, striving to make our very existence a tribute to our Creator. Every good, moral, admirable decision makes the lives of those around us fuller and happier and the world a better place.

From this perspective, social harmony is a consequence of many people acknowledging that life has expectations for them and devoting themselves to meeting them. In other words, it means that internal harmony must be present before we can contribute to social harmony. The greater the number of people who lack internal harmony, the greater the disharmony in society.

The purveyors of anger and hatred dispute Frankl’s idea that we should take responsibility for our lives. They argue that our lives are largely out of our control. He responds that we always have a measure of control, adding that not even suffering or death rob our lives of meaning. Instead, by giving us the opportunity to be noble, they contribute meaning. In his view, it is not just the “uniqueness of an individual life as a whole that gives it importance, it is also the uniqueness of every day, hour, moment” that creates responsibility for us. When we fail to meet that responsibility, its benefits are “forfeited for all eternity.” Only by seizing the moment can we achieve the benefits and make them a permanent part of reality beyond death.

Frankl offers this quote from Goethe—“There is no predicament that cannot be ennobled either by an achievement or by endurance”—and then adds “Either we change our fate, if possible, or we willingly accept it, if necessary.”

Although Viktor Frankl wrote as a scholar with credentials in both psychiatry and philosophy, he was also a religious man who, when given the opportunity to leave Europe and escape Nazi concentration camps, chose to follow the commandment “Honor thy father and thy mother” and stay with his parents, who could not leave and were soon imprisoned and died in the camps. In fact, Frankl’s own suffering in the camps, and that of his fellow prisoners, provided him the insights he later shared with several generations around the world. The books mentioned here and his other works derive from both his intellectual brilliance and his religious faith and offer a dependable guide to restoring social harmony.

* Yes to Life and Man’s Search for Meaning are available at Amazon and bookstores.

Copyright © 2022 by Vincent Ryan Ruggiero. All rights reserved